By Mo Allie

Cape Town – It’s hard to believe, given the subsequent glut of runs he made at provincial level, that Sedick Conrad only started playing club cricket at the relatively advanced age of 18.

Prior to donning the whites of Claremont-based Vineyards CC, Conrad’s weekends in summer would normally be taken up by a train ride from Newlands, where he lived, to Kalk Bay where he and a group of friends would spend their time swimming in the relatively cool waters of the Indian Ocean.

It was only the persistence of his cousin Rushdie Conrad that persuaded “Dickie”, as he was affectionately known, to follow in the footsteps of his father Karriem “Kokkie” Conrad, a top left-arm seamer who played provincial cricket in the 1940s.

From the time his bat became more important to him than his swimming trunks Conrad committed his energies to fulfil his rich sporting talent. As a fly-half for Claremont-based Primrose, he would spend hours practising his kicking skills with his close mate Viccie Christian, who would go on to represent City and Suburban’s provincial side in the non-racial SA Rugby Union’s competitions.

The pair would use some tightly wrapped paper fashioned into the shape of a ball and held together with tape, which they used to hone their kicking skills on a field known as “Die Landjie”, which was situated next to the Liesbeek River where the parking lot for Newlands Rugby stadium is currently located.

To sharpen his batting technique Conrad, who had by then invested himself fully in his cricket career, built a concrete practice pitch on an open field next to his parents’ home in Lansdowne where they had moved to after being forced out of Newlands by the devastating Group Areas Act.

“I spent hours batting on my concrete strip against the bowling of my brother Toufiq and cousin Sharkey. Later the strip was even used for practice by the visiting Eastern Province team during the 1968 Dadabhay tournament in Cape Town. They were staying across the road and when they saw the strip they asked if they could use it,” he told me during an interview for the book More than a Game.

Conrad, who passed away on Tuesday 11 March aged 83, rose swiftly through the ranks after initially starting out as a seamer for Vineyards who played in the Green Point Track-based Western Province Cricket Association.

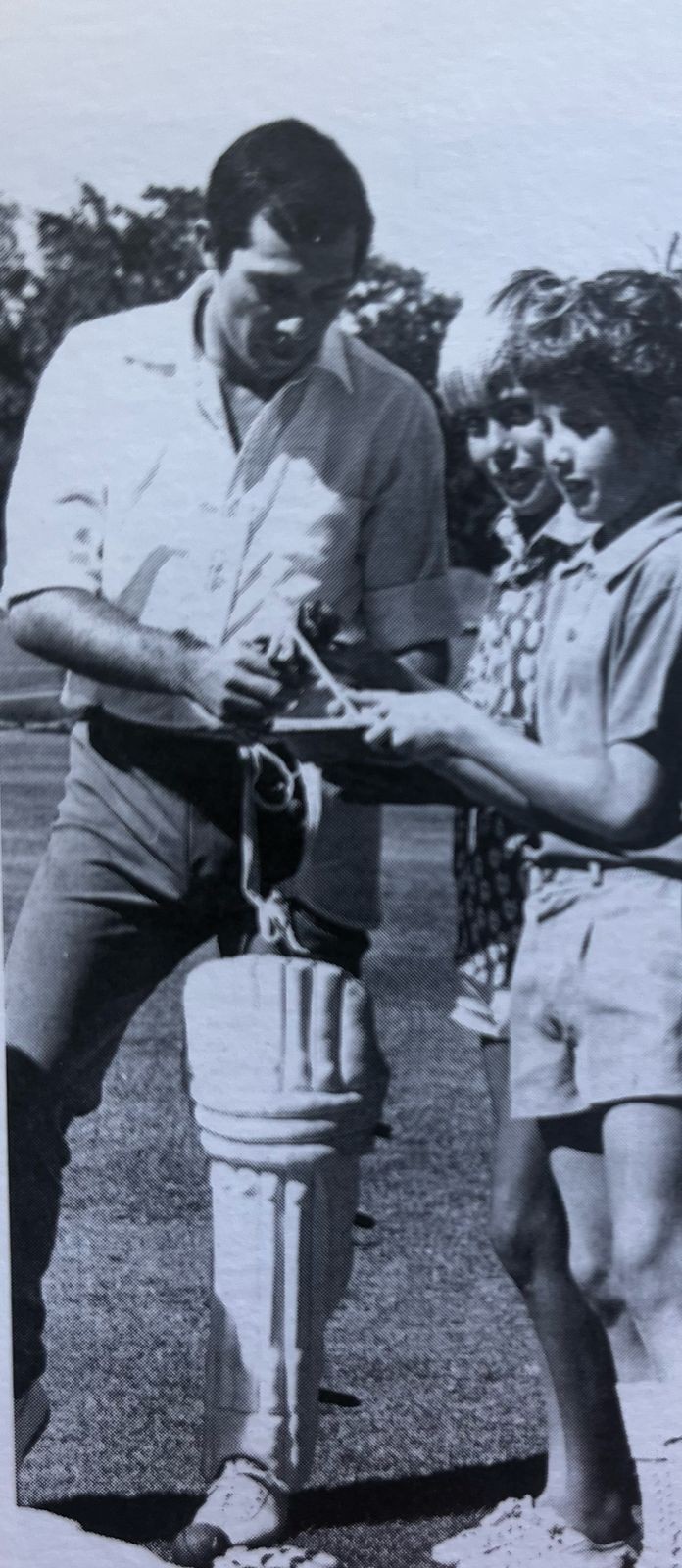

Dickie Conrad at the Newlands nets before the game against the Derrick Robins XI in 1975 Photo: Supplied

A naturally talented player, the hours of practice certainly paid handsome dividends as it took him a mere three seasons to force his way into what was a very strong WP Cricket Board team that played in the second centralised Dadabhay tournament in Port Elizabeth, now Gqeberha, in 1963. The 1960s to mid-70s was the golden era of cricket in the SA Cricket Board of Control (Sacboc).

Conrad fondly recalled how he, together with Suleiman “Dik” Abed and Des February were “the babies” of a triumphant team led by the great left-arm spinner Owen Williams, who had returned from a successful season with Radcliffe in England’s Lancashire League.

Being selected in that team, regarded by many as the best ever WP Cricket Board team, manifested Conrad’s class as it included Williams, Coetie Neethling, both members of Basil D’Oliveira’s SA team that toured Kenya in 1958.

Other top players included Lobo Abed (rated by Dolly as the best wicket keeper in the world at the time), the stylish Neville Lakay, Alan Maclons, a feared pace bowler, and wily spinner Gertjie Williams.

A half-century in the victory against South Western Districts helped WP to claim their first Dadabhay title as he finished the tournament with a modest average of 31.20.

It was at the next Dadabhay tournament in Durban that Conrad gave expression to his talent as an opening batsman with an insatiable appetite for runs.

He was only denied a double century by a bizarre runout involving the eccentric Joey Lambert when within reach of the cherished landmark as he made 194 against Griqualand West.

In three Dadabhay tournaments he made 719 runs at a very decent average of 47.93 per innings.

When the era of 3-day cricket was ushered in by the Sacboc in 1971 Conrad bookmarked the occasion by scoring a polished 139 on his first class debut against Transvaal at Natalspruit in December 1971.

He then followed it up with a magnificent 166 against the same opponents in January 1973. In a record second wicket partnership of 232 with Viccie Moodie (100), Conrad enthralled the crowd at the Rosmead Sportsground in Claremont with a stunning innings in which he demonstrated his ability to employ the rapier and the paintbrush with devastating effect.

He was forced to miss the intervening games against Natal and Eastern Province after his employers, Mobil (which became Engen in 1993), refused to give him time off work.

It was in 1970 that the stocky opener followed a growing number of WPCB cricketers, initiated by Basil D’Oliveira in 1960, who spent their winters playing as the club professional in England’s Lancashire League where the clubs generally engaged established test players as their professional for the season.

Thanks to a recommendation by close pal Dik Abed, who was voted Enfield’s All-Time Great on the occasion of the centenary of the Lancashire League in 1998, Conrad spent a season with Leyland Motors.

Not surprisingly, coming from sunny Cape Town and having played only on matting wickets, he initially struggled to adapt to the chilly conditions and the bowler-friendly turf pitches.

Once he acclimatised and he discovered that the sun could indeed shine in the north of England his form improved. Turning out as a guest for Salford University he made a polished 140 against the Lancashire Second XI at Old Trafford. He did well enough with Leyland to be offered a contract to return but turned it down as his wife Amina didn’t relish the prospect of accompanying him.

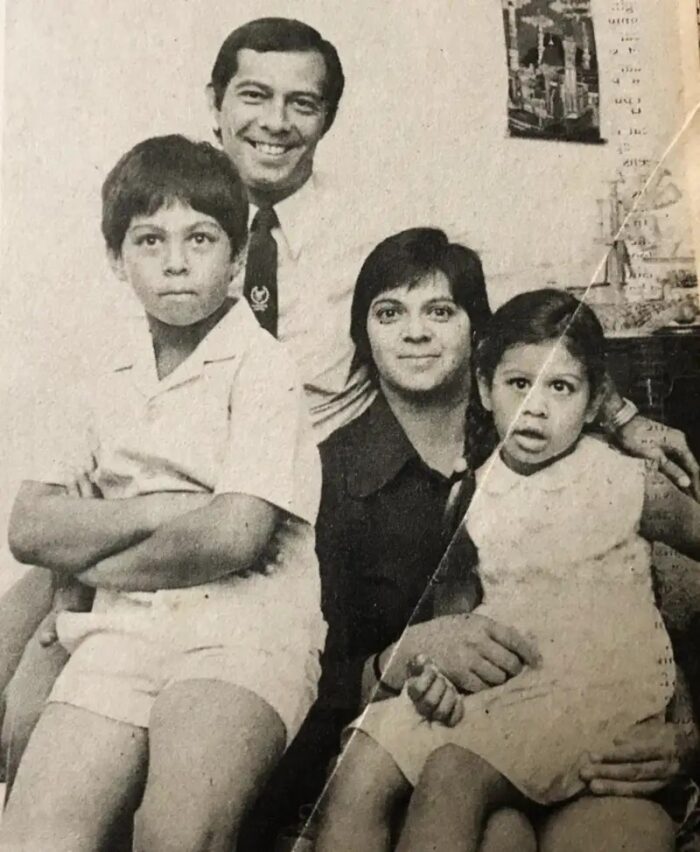

Dickie Conrad with his wife, Amina, their son Shukri and daughter Rukaya. Photo: Supplied

Back home Conrad took over as captain of a WP team that failed to win any of their first three first class games as he initiated an immediate turnaround helping them to share the inaugural 3-day Dadabhay series with Natal in 1973.

Conrad’s career in Sacboc was cut short by a political misdemeanour that saw him being stripped of the captaincy and banned by the WPCB.

After being sanctioned by WPCB president Hassan Howa for watching a game between the international Derrick Robins XI and an SA President’s team at Newlands in 1973, Conrad became the first black cricketer to play in the previously all-white WP Cricket Union’s first division when he turned out for Green Point CC in a team that included England opener Graham Gooch and star WP batsman Hylton Ackerman in 1975.

His performances warranted selection to WP ‘B’ team, a clear indication that this could have been a step towards the senior provincial team. When Green Point CC questioned the reason for Conrad’s continued omission from the senior provincial team they were told he was not considered for selection to avoid to save the union from becoming entangled with the National Party government’s apartheid laws.

He later played in the SA President’s XI, captained by Eddie Barlow and including the likes of Graeme Pollock and Barry Richards, against the Derrick Robins XI at Newlands in March 1975. Disappointingly, coming in at an unfamiliar No7, he made only a single before having his stumps rearranged by West Indian medium pacer John Shepherd.

“It wasn’t easy to adapt to playing in front of a packed ground at a venue like Newlands. I was very tense and besides that, at the age of 33 my better cricketing days were behind me.”

With the anti-apartheid struggle gaining momentum following the Soweto uprisings in June 1976 and the isolation of white South African sport employed as a powerful tool in dismantling the abhorrent system, Conrad’s move to play “normal cricket” was viewed in a very dim light by his community who gave him the cold shoulder.

Like many of his peers, Conrad was keen to test himself against the top white cricketers but coming at a time when the apartheid government had adopted a strategy of window-dressing to hoodwink the outside world that things were changing in the country his timing, for once, was dubious.

“With the benefit of hindsight I realised that I was being selfish. Playing on the other side was not the right thing to do especially at such a sensitive time in our history,” he told me during one of our regular chats.

While he did not have the satisfaction of having the opportunity showing the rest of the world the vast reservoir of untapped talent that existed in the ranks of non-racial cricket at the time, at least he had the consolation of seeing his son Shukri taking charge of the Proteas as coach.

“You can see the team is really playing for Shuks,” Conrad told me after the team’s victory over Pakistan at the end of last year when they qualified for the Test Championship final against Australia in June.

Sadly, he won’t be around to witness the historic occasion.

Conrad is survived by his son Shukri and daughters Rukaya, Thuraya and Warda.